What is the history of your favorite food? That depends upon the food and how deep you want to dig. Take tiramasu. This dish was "created" in the late 20th century. You could find a few magazines articles confirming period popularity/origination and stop there. Or? You could go the next level and research the recipe based on composition. You would soon discover this dish was based on Victorian-era moulded creams which were based on Colonial-era tipsy cakes which were inspired by Renaissance-era trifles.

EVOLUTION VS. INVENTION

Very few (if any) foods are invented. Most are contemporary twists on traditional themes. Louis

Diat's famous Vichysoisse was a childhood favorite. Today's grilled cheese sandwich is connected

to ancient cooks who melted cheese on bread. 1950s meatloaf is connected to ground cooked

meat products promoted at the turn of the 20th century, which are, in turn related to ancient

Roman minces. Need more? Corn dogs and weiner schnitzel. French fries and Medieval fritters.

New York gyros and Middle Eastern doner kebabs. Hershey's Kisses and ancient Incan cocoa.

Where to begin?

Check food history encyclopedias and dictionaries. Standard sources noted here. Cuisine/period

cookbooks and history sources may also be helpful.

Advanced techniques

One of the most challenging aspects of recipe research is identifying common themes and making

connections. A survey of cookbooks through time often reveals similar recipes with different

names. A careful inspection of ingredients and cooking instruction confirms or refutes culinary

lineage. To complicate matters, variant spellings often appear in older texts. Of course, the first

"real" appearance of any recipe often predates the first occurence of recorded in print by several

years.

1. Examine old cookbooks.

Work your way back from the current recipe. Look for similarities in ingredient and method.

BEWARE. Recipes change names.

2. Research the history of each ingredient.

Old

world or new? Rare commodity or common ingredient? Apple pie is an American icon, but apples

aren't native to our country. Tomato sauce is the cornerstone of many popular Italian dishes, but

these fruits (as they are botanically classed) weren't known to Europe until the 16th century. West

African Lemony Chicken Okra Soup. Some foods (rice, beans, pork, bread, soup) are nearly

ubiquitious. These recipes evolved according to ingredient availability, technological

advancement, and local taste.

PRODUCT HISTORIES

If the product is still being made, start with the U.S. Patent &

Trademark Office database. This provides the date of first introduction, original manufacturer

and

(usually) current trademark holder. Corporate "biographies," article databases, product histories,

and company Web sites often provide details on the product's introduction, market strategy,

consumer trends, variations (the iterations of Oreos), packaging, and pricing. Anniversary articles

(100th anniversary of Jell-0 celebrated in 1997) often provide excellent overviews.

"LOST RECIPES"

Family favorites can sometimes be recovered. It is very helpful if you have some idea of recipe

origination: cookbook, magazine article, newspaper clipping, radio/television show, "back of the

box," contest winner? Where did the cook usually get her recipes? Where and when (1930s

Quebec) is important for tracking local fare. The cook's ethnic heritage (Polish Jew, French

Canadian, West African) is crucial for locating "grandmother's traditional" recipes. Sources: old

cookbooks, recipe exchanges, community cokbooks, period magazines & local newpapers.

RESTAURANT DISHES

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

Sometimes the answer to a food history question is straightforward and easy to confirm (the

ingredients of the original Dagwood sandwich).

Other times the answer is a tasty puzzle (Club

sandwiches) with conflicting pieces. And then? There are questions for which there are no

satisfactory answers

(Who named the "monkey dish?"). There are

times when the best one can do is assemble as much information as possible and make educated

guesses based on supporting historical evidence. Croissants, ice cream cones, pink

lemonade...culinary lore abounds.

In short, food history is not a "piece of cake."

Need to construct a more detailed/updated new food product timeline?

How do recipes get their names?

People (Lobster Newberg, Reuben Sandwiches, Chicken Tetrazzini, Fettuccini Alfredo)

I have an old cook book without a cover or title page, is there a way to identify it?

Cook books used in Early America were published in Europe and major urban American centers: New York., Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore. Recipes in those days were often

copied verbatim from one author to another (forget trademark infringement!). Please note: many popular cook books through time offer several editions, revisions,

publishers, and authors. We would be happy to help you determine an approximate date/identify your cookbook if you are willing to share information outlined above. It would also help if you could scan a few sample pages with the popular recipes. Who knows?

We might be able to match it up!

I have a manuscript cook book. How can I tell how old it is?

Standard scholarly protocol for examining/reading manuscript cook books for presentation to modern audiences includes:

Want to recreate these old recipes? Our notes on interepreting & adapting vintage recipes.

How much is my old cook book worth?

Please note: the value of old cook books, like anything else, is based on what buyers are willing to pay. Most mass produced

cookbooks from the 20th century have low value on the open market. Of course, there are exceptions. Autographed copies,

first editions, limited or special editions, are generally worth more than subsequent counterparts. Pre-20th century cookbooks

generally have more value because they are harder to find.

In all cases, condition of the item plays a key role in determing value. Original binding, covers, dust jackets, no missing

pages, no writing (unless the owner was famous), no stains or obvious wear.

Whether you're selling or buying, it pays to do your homework!

Who designates "national" food days?

Tools for research:

How do I become a food historian?

Where do food historians work?

Culinary history organizations meet in some cities. They offer educational programs, topical lectures and

excellent networking opportunities.

Some food historians join the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP).

This organization offers a food history roundtable. It also manages the

Culinary Trust, a non-profit organization devoted

to preserving our culinary treasures and promoting scholarly research projects.

What's the difference between a food historian and a culinary historian? The latter is also a professionally trained chef.

The first group can study it; the second group can actually cook it. More or less.

Who is Lynne Olver? She herself said "

Note: Ms. Olver is not a chef. Culinary

training (if you call it that!) was a 4 year stint as a short order cook in college. She is an intuitive cook who views recipes

as starting points for personal inspiration. Her dishes have no recipes, no

names. Some work out better than others. None of them can be replicated.

If we're lucky, life gives us a few delicious chances to experiment. When the results taste good, huzzah!"

About culinary research & about copyright

Signature recipes from famous restaurants fall into three categories:

Researching the history of a specific cuisine, recipe, food, or product often requires using a

variety of sources to develop a complete and accurate picture. Depending upon the question, the

answer may require:

Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America/Smith, Oxford Companion to

Food/Davidson, An A to Z of Food and Drink/Ayto,

Cambridge World History of Food/Kiple & Ornelas, Food in the Ancient World from

A to Z/Dalby, History of Food/Toussaint-Samat, The Encyclopedia of American

Food and Drink/Mariani, American

Century Cookbook/Anderson.

Oxford English Dictionary, Dictionary of

Americanisms/Mitford, Dictionary of American Regional English/Cassidy, I Hear

America

Talking/Flexner

The Story of Corn/Fussell, The Tomato in America/Smith, The True History of

Chocolate/Coe, A Social History of Tea/Pettigrew, Uncommon Grounds: The

History of Coffee and How it Transformed our World/Pendergrast. Identify titles with the

Library of Congress catalog. Your librarian can help you

obtain the books.

America's First Cuisines/Coe, Food and Feast in Tudor England/Sim, Food in

Early Modern Europe/Albala, A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food/K.T. Achaya,

Food and Drink in Britain: From the Stone Age fo the 19th Century/Wilson, Classic

Russian Cooking/Toomre, Jewish Cooking in America/Nathan

How Products are Made, Encyclopedia of Consumer Brands,

magazine/newspaper/trade journal databases are great places to find "lost recipes." Ask your

librarian about access. New York Times Historic, EBSCO's Masterfile,

ProQuest's NewsStand, and Factiva. Scanned newspapers (Proquest Historic,

NewspaperArchive.com, & local collections include advertisements, making them best sources for

retrieving recipes published in food ads, commercial product names, and historic prices.

Origin of Cultivated Plants/De Candolle

JSTOR, Dissertation Abstracts, Historical

Abstracts, America: History & Life, Sociological Abstracts, Agricola

Libraries, museums, historical societies, living history museums & industry/company archives.

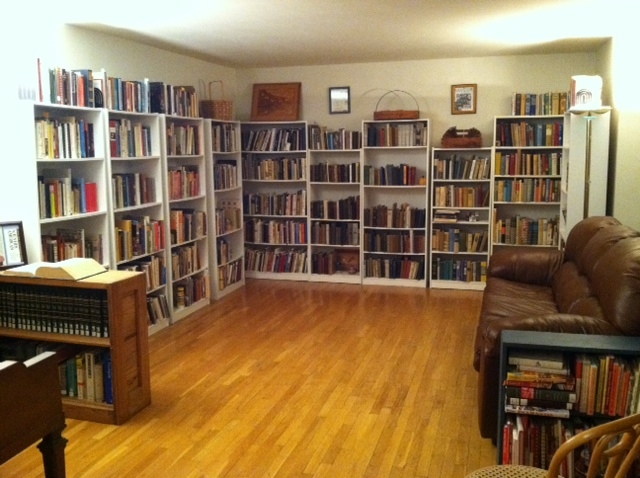

Outstanding culinary history library collections (U.S.): Harvard/Schlesinger, University of Pennsylvania,

Cornell University, Johns Hopkins University, University of Iowa, Michgan State University, New

York Academy of Medicine, New York Public Library, Los Angeles Public Library & The Culinary Intitute of America (Hyde Park).

Culinary researchers, foodways curators, chefs, professors, government

officials, corporate information officers, book authors, historical reenactors (Society for Creative

Anachronism=Medieval food specialists).

These are uploaded by food manufacturers, research institutions, food media sites, and private

individuals.

There are several sources you can use to construct your own food product timeline. Sources vary according to your definition of "food invention" (brand new

product, or variation of extant line (mini oreos) and purpose of your project. Yes, this is research!

If you need new USA commercial food products, year-by-year we suggest you check:

If you're looking for restaurant food innovations & trends,

The National Restaurant Organization is your best bet for data.

...keyword search "new food" or the manufacturer's name with the word new [kellogg's and new]. There you will get new product announcements, advertising notes & marketing strategy. Ask local public librarian how to access.

...some offer company history/timeline detailing major innovations & new products. Press release archives announce new items.

...search by company (owner/patent assignee) or classification/limit by date).

...expensive!

NPD Foodworld is one of the most well known. Published reports are not available in public libraries.

...trade journal devoted to Food & Beverage industries.

...google (trade show food) to identify shows featuring new food products & innovations.

Some food categories have their own associations & trade show. EX: Snack Food Association.

How are recipes named? Great question with several answers. Recipe names celebrate, commemorate, elucidate, and entice.

Recipes are named by chefs, restauranteurs, food companies, test kitchens, home cooks and contest winners. Recipes named for people generally fall into two categories:

celebrities and family members/frequent patrons of the chef/restaurant owner. Consider:

Places (New England Clam Chowder, Manhattans, Rocky Mountain Oysters, Waldorf Salad, Dover Sole, Frankfurters)

Events (Chicken Marengo, Coronation Chicken, Earthquake Cake)

Cooking method (Coq au vin, Fondue, New England Boiled Dinner, Tuna Noodle Casserole, Flower Pot Bread, Corned Beef)

Classic French designations (Florentine=spinach, Poivrode=black pepper, Chiffonade=thin cut slices)

Descriptive (Asparagus with Hollandaise Sauce, Fried Onion Burgers, Memphis Dry Ribs, Chilled Cucumber Soup)

Ethnic/cultural attributions (Irish Soda Bread, German Potato Salad, French Dressing, Russian Tea)

Company promotions (Knox Perfection Salad, Nestle Toll House Chocolate Chip Cookies, Kool-Aid Pickles)

Shape (Flat-iron steak, Grape Tomatoes, Lemon Squares)

Texture (Cream cheese, Mille Feuilles, Wilted lettuce, Fruit Leather, Chiffon Pie)

"Looks Like" (Ciabbata=slipper, Elephant Ears, Cats Tongues/langues de chat, Mud Pie, Ox Eyes)

"Tastes Like" (Mock Apple pie, Mock turtle soup)

Foreign & Indigenous borrowings (Barbecue, Waffles, Kabobs, Quesadillas, Yogurt, Escabeche, Jambalaya, Sofki)

Body parts (Head Cheese, Pigs Feet, Ox Tails, Spare Ribs)

Flavors (Sweet & Sour Pork, Pepper Steak, Honey Mustard)

Key ingredient (Tapioca Pudding, Beef a la Mode, Chicken Salad, Cornbread, Key Lime Pie, Navy Bean Soup, Gingerbread)

Contests (SPAM, Tunnel of Fudge)

Holidays (Christmas Pudding, Easter Ham, New Year Cookies)

Origin stories (Ice Cream Sundaes, S'Mores)

Intrigue (Impossible Pie, Zombies, Wacky Cake, Rocky Road, Red Velvet Cake, Pop Rocks)

If your cook book has no standard identifying standard marks (title page, publishers marking/imprint, author, location) you might still be able to identify it. We find books like

this from time to time. Physical description notes in catalogs of major collections (national libraries, university libraries, special collections housed in archives and

museums) are gold.

If your book is completely manuscript (hand written) then recipes are your best clues. Also...where/when was the item purchased. Can you trace to possible original

owner (either documented or by inference)?

Manuscript cook books are indeed rare and special finds. Decoding origins pose interesting challenges. As we turn the pages of this very personal

piece of history, we wonder: who wrote this book and why?

Recipe measures (butter the size of a

walnut, No. 2 cans), cooking instructions ("until done," "hot oven") and kitchen tools (hoops, Mary Ann pans) are standard tools for identifying general period.

A. Complete list of recipes...cross indexed by type.

B. List of ingredients...indicating frequency of reference. This suggests items commonly used by the author/readily available.

C. Cooking terms & instructions...bake, fry, "until done."

D. Weights & Measures...butter the size of a walnut, 3 pounds flour.

E. Headnotes & introduction...author, provenance, how obtained.

F. Transcription & original images...exact transcription vs slightly redacted to assist modern readers.

G. Glossary...archaic terms (pie plant, paper of cornstarch) & radically different/variant spellings require explanation.

H. Modernized recipes?...nice addition of the book is intended for general readers/home cooks. If you do not have culinary training, hire a professional recipe

developer to supply workable directions.

The Food Timeline DOES NOT provide valuing services. Those services are provided by professional

antiquarian

booksellers, licensed appraisers, and auction houses. Free online sources for approximate values are used booksellers

(Alibris, AbeBooks, UsedBookCentral, etc.) and EBay. Antique Trader's Collectible Cookbooks

Price Guide/Patricia Edwards & Peter Peckham, provides price ranges for selected popular American books. Used/old book

stores often have sections devoted to cookooks; check to see what the "going" retail rate is. Check item carefully for year

published and edition.

"National" days (food or otherwise) are declared by one of three sources:

1. Federal government (USA=Presidential Executive Order (EO) or Dept. of Commerce) designating a day,

week, month dedicated to a particular

topic. There is no limit to the number of EO in any given month. Topics are selected by legislators and organizations who want to promote awareness

(School Lunch Month) or economic activity (a food designation generally promotes folks engaged in agriculture, transportation, retail and/or foodservice).

EOs can be issued annually (Thanksgiving Proclamation) or one time. EO online.

2. Industry associations declare national days to promote products. Example: National Sandwich Day.

3. Companies declare national days to promote their products. Example: Iced Tea Week.

4. Charities & not-for-profit organizations. Example: the original Doughnut Day.

1. Chase's Calendar of Annual Events (found in many public libraries, but it is a challenge to find a library with a backrun). Entries are arranged by day, indexed by title and subject. Entries provide information regarding the originator of the day. Use Chases to track first and last instance of a particular day. This is interesting and detailed research because some "national" days actually change date and sponsor.

2. Historic newspapers (National and local) are great sources for announcements and details, especially regarding ad campaigns and/or contests. Your local librarian can help you access.

3. NOTE: Many "national" food move throughout the calendar through time. Today's "first Friday in June" might have been

"last Tuesday in October" back in the day. Likewise, sponsorships and purposes can change from original intent to current mode.

Food historian is a niched career field. That's why you won't find information on

what we do and where we work using standard career reference sources. While some schools (universities/culinary

arts schools) offer classes in food history studies, there

is no certification or specific degree for this career. [NOTE: some universities offer graduate degrees in

gastronomy.] Many practictioners

(but not all) have college/advanced degrees. These degrees center on history,

anthropology, women's studies, English literature, sociology and library science. We are drawn to food history for different

reasons. In some cases, food history "chose" us.

Please note: many professional food historians have full-time "day" jobs to pay the bills.

A food historian with a masters in library

science, Lynne created the Food Timeline in March 1999 and over the next 14 years welcomed 35 million readers

and, at no charge to anyone, answered 25 thousand questions.

She worked regularly with students, teachers, media, culinary professionals, cook book authors/editors,living history museums, and the general public

worldwide providing

original content, background material, fact checking services, and document delivery. She was regularly tapped by

journalists writing for the Wall Street Journal, New York

Times, NPR,

America's Test

Kitchens, Cooks Illustrated, Sunset, and Saveur. The Food Timeline was awarded

Saveur 100 recognition (2004). Details on the FT's origin and evolution chronicled by

Heritage Radio (Brooklyn NY) & Culinary Types/TW

Barritt. Ms. Olver was a contributor to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America (Second Breakfast, Mock

Foods) and Gastronomica "The Truth About Clams Casino".

Her FoodTimeline library owned 2300+ books, hundreds of 20th century USA food company brochures,

& dozens of vintage magazines (Good Housekeeping, American Cookery, Ladies Home

Journal &c.) Lynne Olver died April 14, 2015, age 57.

Research conducted by Lynne

Olver, editor The Food

Timeline. About this site.